If I

learned anything about life during college, it was to turn away from my

shattered ego and move on.

If I

learned anything about life during college, it was to turn away from my

shattered ego and move on.

Notes

of a Crocodile describes the

college years of a young gay Taiwanese woman, her various lovers and friends

during the later 1980s and early 1990s in Taipei. Like most coming-of-age

novels it describes the heartbreak of youth, the gaining of experience through

the harsh blows of the world, the exaltations and despairs of first love, the

gradual coming together of a sense of self, of a sense of destiny. And like

most coming out novels it describes the sense of isolation from society as the

first realisations of same sex desire dawn, the sense of an already fragile,

fledgling egohood rendered even more precarious by the knowledge of an

otherness, the knowledge that one is becoming an unwilling transgressor against

society.

Lazi (pronounced lah-dze) and her friends

spend their lives in the time honoured fashion of students everywhere: falling

in and out of love, reading, attending classes, doing assignments, bickering,

sleeping and earning pocket money, and analyzing every nuance of their

relationships in midnight conversations. Their adventures are presented as a

series of achronological entries in eight notebooks. The entries include

reportage, love letters, records of conversations, sly vignettes and lyrical

descriptions of Taipei, fragments, diary entries; the style ranges from the face-burningly

personal – one or two of the love letters had me wincing – to the sardonic,

from the wittily epigrammatic to a kind of freewheeling prose poetry. Imagine

Haruki Murakami meets Banana Yoshimoto meets Rimbaud. Some sections appear to have

been written right after the events, or even as those events unfold, giving

them a rawness, an immediacy that can be quite unsettling, while others appear

to have been written long after and come with the benefit of hindsight and

reflection. The emotional intensity is relieved by satirical newsflashes about

a plague of crocodiles that has overtaken the nation. Citizens are urged to

exercise caution and be on the lookout for crocodiles wearing human suits and

posing as real people. There is a hotline for callers to report sightings…

However, some of the entries often come

across as being the mere rantings and bleatings of a rather self obsessed,

overeducated but underloved overgrown child; a girl who has not yet learned the

harsh truths about growing up,: that you are not as important and as unique as

you think you are; an artist who has not yet learnt how to distance herself

from her experiences to make them truly universal, (a kind of Taiwanese Sylvia

Plath). At times, the novel seems to be little more than a ‘lightly

fictionalized autobiographical account’ (words which must make many an editor’s

heart sink) of growing up in Taipei. The

fragmentary form of the novel only reinforces this impression of something half

finished. One wonders, on first encounter with this text, what interest, what relevance,

the half-baked descriptions of the trials of a college student from Taiwan can

have for a reader with no knowledge of Taiwan or of Lazi’s milieu, beyond the

obvious curiosity factor. One wonders also as to the book’s and the author’s

cult status here in Taiwan.

Well. The narrator is highly intelligent,

highly literate and highly self aware. There are references to Western

literature and culture (but strangely, almost none to Chinese writers and

culture). At one point when the narrator is torn between her desire for total

solitude and her desire for social interaction, she wittily describes herself

as clutching her copies of One Hundred

Years of Solitude in one hand, and Lust

for Life in the other. The form of the novel is said to have been inspired

by the techniques of Derek Jarman and Genet. The translation is very good

indeed: Bonnie Huie does an excellent job of capturing in English the Chinese

speech patterns in the long stretches of dialogue, and even manages to convey

some of the word play and puns that Lazi and her friends indulge in.

For Lazi’s is not only a queer coming of

age, but a search for a self in existentialist terms that speaks directly to

many (young) people in Taiwan, of whatever orientation. Lazi writes:

Most people go through life without ever living. They

say you have to learn how to construct a self who remains free in spite of the

system. And you have to get used to the idea that it’s every man for himself in

this world. It requires a strange self-awareness, whereby everything down to

the finest detail must be performed before the eyes of the world.

College in Taiwan represents the first time

Taiwanese youngsters can take a breather from the utterly relentless round of

examinations and cramming that has marked their childhood and early

adolescence, and deal with the pleasures and the pains, the stresses and

strains of growing up. This is not so much to say that Taiwanese are late

developers in that sense, but more to note how the search for identity and a

role in life preoccupies Western teens at a much earlier age when perhaps their

ability to articulate their feelings has not caught up. Happening later, in

their college years, Taiwanese are more able to articulate their dilemmas, to

themselves and to their friends, and their diaries.

Reconciling the desire for

self-determination and the need to meet parental and social expectations is a

highly stressful and difficult balancing act that many highly educated young Taiwanese

experience as an existentialist dilemma, as do the characters in the novel. One

of Lazi’s friends articulates this as coming up against the wall of absurdity, a description that references both Sartre

and Camus, and Dostoevsky. Another, marginal, character, a boy named Nothing by

his friends, has scarred his face with a knife in episodes of self harm:

He vowed to cut through the other self that had been

handed to him by other people. It wasn’t the real him. Then he traveled around

the world with just a backpack and became his true self.

The existentialist dilemma is most

particularly marked in two overlapping areas: family expectations, and gender

roles. Lazi writes of her relationship with her family:

I let them form a new image of me. It’s been a

constant struggle. I’ll always feel love for them and have basic needs to be

met, so it takes courage to draw the line. But if I don’t, my love for them and

my needs will become bargaining chips that I have to exchange for my

independence.

Lazi is studying Gabriel Marcel, the French

Christian existentialist, (who is also a key influence on Qiu Miaojin’s final

book, Last Words from Montmartre) one

of whose main concerns was how an individual can create and maintain loyalty (fidelite) to a group without

compromising their existential selfhood. Marcel’s concept of fidelite can stand in for the Chinese

concept of filial piety (xiàoshùn

孝順). It’s telling that Lazi and her

friends turn to Western works rather than Chinese works to help them deal with

their crises, presumably because the Chinese classics with their emphasis on xiàoshùn孝順will be no help to them.

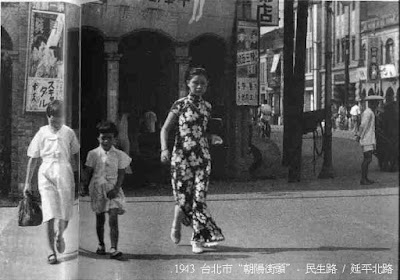

Qiu Miaojin was writing in a time when

Taiwan was only just beginning to make the transition from martial law, into what

it is today: one of the most forward looking democracies in Asia, with a woman

president, with firm and unquestioned rule of law, equal opportunities for both

genders, the biggest Pride festival in Asia (an estimated 100,100 attended this

year’s event) and a well-coordinated and vocal LGBT rights movement that has

recently secured from the Supreme Court a ruling that will make same sex

marriage constitutionally legal in two years, so far the only country in Asia

to do so. However, back in the late 80s/early 90s, Lazi revolts when she

considers the traditional gender roles that have been assigned to her. Human

relationships and mutual attraction, she writes, are based on the gender binary, which stems from the duality of ying

and yang, or some unspeakable evil. But humanity says it’s a biological

construct: penis vs, vagina, chest hair vs,. breasts, beard vs. long hair….

Male plugs into female like the key into lock, and as a product of that

coupling, babies get punched out. Those who don’t fit into the traditional

gender categories are cast into the

freezing cold waters outside the line of demarcation, into an even wider

demarcated zone.

Against this negativity, however, Qiu

Miaojin peoples her novel with characters who are gender fluid and who extend friendship

to each other as they inhabit this wider demarcated zone, creating their own structures

of love and loyalty, their own alternative queer family. The burgeoning gay

scene of the period is described in terms that are remarkably prescient. When

Lazi visits an underground club with a male friend, he tells her: Those people are all genderless. Or maybe I

should say, they’re opposed to being bound by simplistic signifiers of gender….and

in another conversation, one of the characters drunkenly proposes that they all

try to establish post-gender relations with each other. Family and gender are

aligned towards the end when Lazi’s friend Meng Sheng tells her: We come from a long line of deviants

throughout history, a queer alternative to the ancestors that are an

essential part of every Taiwanese family.

The form of the novel now starts to make

more sense against this exploration of ‘existentialism with Chinese

characteristics’ that is the main theme of the work. 手記 literally translates as ‘hand notes’. The book has all the

appearance of having been written on the hoof, but this is merely an artifice,

one that has been constructed to convey the impression of having being written

on the hoof, a performance before the

eyes of the world. In this it has much in common with European and American

existentialist texts.

A close parallel in Western literature

would be to that other great teeny angst bildungsroman, The Catcher in the Rye, with which Notes of a Crocodile shares a sense of outrage against the fakeness

of an adult world, a sense of disgust against societal norms, and a similar

freewheeling cynical style. Like death,

college serves as a kind of escape hatch. But while death takes you straight to

the morgue, college is a single rope dangling loose from the inescapable net of

society. Like Notes of a Crocodile,

Catcher in the Rye is a performance.

Written by a thirty two year old man as an extended exercise in a literary

technique known as skaz, this novel has often been mistaken for a cry of

authenticity, and the unsophisticated (or simply the very young) often mistake

Holden Caulfied’s rants as ‘the real thing’. Likewise, Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, and Sartre’s Nausea, both good examples in view of

Lazi’s existentialism, also purport to be authentic cries of a tortured soul.

But these novels are only posing as such; their real purpose is to render

through artistic means a philosophical position. Their first person narrative

and fragmentary form is literary Expressionism, not to be mistaken for the

author’s voice and personal experience, but to be read as the expression of a

fictional creation. It’s this quality of spurious authenticity that gives these

works their great power and status as works of fiction, or in the words of Jean

Cocteau, ‘the lie that tells the truth.’

But there are also parallels in modern

Chinese literature for the performance of authenticity. Notes of a Crocodile has much in common with the famous story by

Ding Ling, The Diary of Miss Sophie,

which also poses as diary/notes, and of course Lu Xun’s Diary of a Madman is another example. Confucius in his commentary

on the Five Chinese Classics praised the three hundred poems in the Book of Songs as having thoughts never twisty. Modern Chinese literature

on the contrary has always valued twisty thoughts – or unconventionalised soul

baring - as a sign of authenticity with which writers can confront the artifice

of the classical tradition. Wang Dan, the Tiananmin dissident, reveals this

when he writes of Qiu Maiaojin’s work that its

excruciating revelation of the author’s innermost self […] is after all what

makes the magic of literature. What makes the magic of this particular

novel is that Notes of a Crocodile

ambiguates the boundary between authenticity and performance: it’s both notes

and a novel about notes.

It’s this ambiguity, allowing us to read

the novel as direct expression, and at the same as directed Expressionism, that

has largely accounted for the status of Qiu Miaojin’s work on the Taiwanese

cultural and literary scene. Winner of the Central Daily News Short Story Prize, the United Literature Association Award, and the China Times Honorary Prize

for Literature, her work appears on college syllabuses, and is the subject of

numerous dissertations. But amongst the general republic of readers she has

inspired rock bands, pop songs, dance pieces, blog tributes, video tributes,

internet discussion groups, and a feature length documentary. There is even a

high school kid reading from her work on Youtube.

It’s hard to resist the temptation to allow the knowledge of her suicide

at the age of 26 in Paris in 1995 to infect one’s reading of the text. In her

last novel, Last Words from Montmartre, also

published by NYRB Classics, the line between authenticity and performance is

even more difficult to place. In that book the Rimbaud element is more to the

fore, as translator Ali Larissa Heinrich notes in his excellent Afterword, and

it’s virtually impossible to read it as anything other than as notes of a

pathology, or as one long extended suicide note. Death and suicide does form a

persistent minor whisper throughout the text of Notes of a Crocodile, but ultimately, Qiu Miaojin ends this work on

a note of hope and uplift.

It’s hard to resist the temptation to allow the knowledge of her suicide

at the age of 26 in Paris in 1995 to infect one’s reading of the text. In her

last novel, Last Words from Montmartre, also

published by NYRB Classics, the line between authenticity and performance is

even more difficult to place. In that book the Rimbaud element is more to the

fore, as translator Ali Larissa Heinrich notes in his excellent Afterword, and

it’s virtually impossible to read it as anything other than as notes of a

pathology, or as one long extended suicide note. Death and suicide does form a

persistent minor whisper throughout the text of Notes of a Crocodile, but ultimately, Qiu Miaojin ends this work on

a note of hope and uplift.

Admitting I have problems is a mode of optimism, since

every problem has a solution. Unhappiness is a lot like bad weather; it’s out

of your control. So if I encounter a problem that even death can’t solve, I

shouldn’t care whether I’m happy or unhappy, thereby negating both the problem

and the problem of a problem. And that is where happiness begins.